LATEST EXHIBITS AT SAAM

UPSTAIRS AT SAAM

GROOMING A GENERATION

A History of Black Barbershops & Beauty Parlors

NOW WITH A DIGITAL TAPESTRY

AUGMENTED REALITY SELF TOUR

Barbering has a long and storied history in the African American community. This exhibit explores that past, shining light on the experiences that led to the building of Mr. Seymour's establishment that now houses SAAM as well as how barber shops and beauty parlors became a natural gathering place to stay connected to culture and ideas.

SHAUNT'E LEWIS exhibition

Originally from Springfield, Massachusetts, Shaunt’e relocated to Indiana in 2011 and has since built strong connections within the community, including collaborations with Visit Indy and the Indy Chamber. As a multidisciplinary artist with background in entrepreneurship and a deep passion for both illustration and fiber art, Shaunt’e continues to expand her creative horizons while inspiring and engaging audiences through her diverse and empowering works.

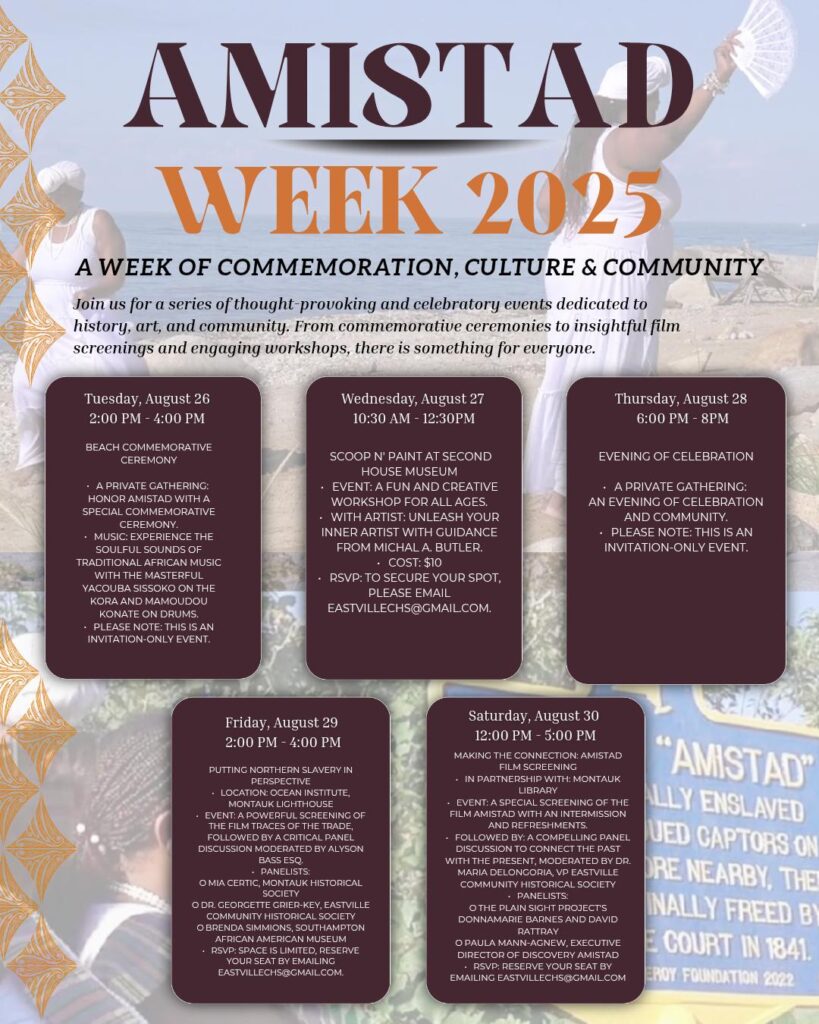

Amistad Week 2025

A Week of Commemoration, Culture & Community

А week-long series of thought-provoking and celebratory events honoring the legacy of the Amistad and celebrating history, art, and community. From commemorative ceremonies to creative workshops, insightful film screenings, and engaging discussions, there is something for everyone.

Tuesday, August 26 | 2:00 PM – 4:00 PM

Beach Commemorative Ceremony (Invitation-only)

• A private gathering honoring the Amistad with a special commemorative ceremony.

• Live music featuring the soulful sounds of traditional African instruments with the masterful Yacouba Sissoko on the kora and Mamoudou Konate on drums.

Wednesday, August 27 | 10:30 AM – 12:30 PM

Scoop N’ Paint at Second House Museum

• A fun, creative workshop for all ages with artist Michal A. Butler.

• Cost: $10

• RSVP required: eastvillechs@gmail.com

Thursday, August 28 | 6:00 PM – 8:00 PM

Evening of Celebration (Invitation-only)

• A private gathering celebrating community and culture.

Friday, August 29 | 2:00 PM – 4:00 PM

Putting Northern Slavery in Perspective

• Location: Ocean Institute, Montauk Lighthouse

• Film screening of The Film Itself: The Trade, followed by a panel discussion moderated by Eastville’s own Dr. Georgette Grier-Key, featuring distinguished guests from the Southampton African American Museum and other historical experts.

• RSVP required: eastvillechs@gmail.com

Saturday, August 30 | 12:00 PM – 5:00 PM

Making the Connection: Amistad Film Screening

• Location: Montauk Library

• Screening of the film Amistad, followed by a Connecting Panel discussion on lessons from the past and their relevance today, moderated by Karma Lemongrass.

• RSVP required: eastvillechs@gmail.com

May 16 - July 7

Courtney Minor

Doors Into My Life

Opening Reception May 30th

A New Exhibition at the Southampton African American Museum, featuring the original art of Courtney Minor.

The Southampton African American Museum proudly announces the opening of “Doors Into My Life” by Courtney Minor, a spectacular exhibition that explores the many doorways into the continuous evolution of Courtney’s life. Through the mediums of self-portraits, tribute, and protest art, Courtney invites visitors to witness her journey of continuous self-discovery.

The exhibition opens on Friday, May 16, 2025, reception on Friday, May 30th and will be on display through Monday July 7th, providing the opportunity to witness a remarkable collection of original mixed media artworks that serve as Courtney’s deep introspection of looking to the past for answers to today.

FEBRUARY 26TH- APRIL 2025

BOTH/AND: AN EXPLORATION OF THE IDENTITIES OF BEING BLACK AND A WOMAN IN THE UNITED STATES.

Featured Artists include:

- The Black Girl Magic Organization from Southampton High School

- Linda Mickens

- Dr. Nichelle Rivers

- Brenda Simmons

With special contributions made by:

- Dr. Georgette Grier-Key

- Frank Bold

ALVIN CLAYTON

July 20th – November 1st, 2024

Alvin Clayton, like his artistry, is an eclectic mix of visual artist, professional fashion model, athlete and restaurateur. But he was always driven to paint from an early age. Like many households, Alvin certainly couldn’t express the desire to become a visual artist as that was not considered a “real” career.

Consequently, Alvin attended college on academic and athletic scholarships, and modeled professionally. When he landed a photoshoot in Paris he discovered French visual artist Henri Matisse.

Alvin was awe-struck, as the use of colors reminded him of his Trinidadian home. He knew then that suppressing the desire to paint was no longer an option, and subsequently taught himself to paint. He was also greatly influenced by renowned photographer James Van Der Zee.

He maintained his newly established painting career throughout his 25 years of modeling where he appeared in GQ, Vogue, Vanity Fair, Ebony, Esquire and Glamour magazines. He was also commissioned to create work for films including, most notably, Why Do Fools Fall In Love, The Gail Devers Story, The Best Man Holiday and The Best Man: The Final Chapters.

His work has also been showcased on CNN and at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. In 1992, Clayton held his first solo show at the Lee Arthur Gallery in Soho. Clayton is collected by Denzel Washington, Halle Berry, Don Cheadle, Blair Underwood, Robert De Niro, CCH Pounder, Hill Harper, Janice Huff, and Kenneth Chenault, to name a few.

Also, important to note, Alvin is the restaurant owner of Alvin & Friends, selected as “Best of Westchester” five times by Westchester Magazine, winner of an Open Table 2017 Diner’s Choice award, and described by The New York Times as a “darling of downtown New Rochelle.”

May 25th - July 8th

Mayowa Nwadike

What Is, What Was and What Could Be

Mayowa Nwadike is a self-taught multi-disciplinary Nigerian artist and primarily a mixed media painter, utilizing acrylic and charcoal to create his sizable works. Focusing predominantly on realism with elements of abstraction, his works are descriptive, not narrative, driven by African stories and symbolism. His work delves into the complexities of toxic masculinity and highlights the challenges immigrants face.

THE BLACK POWER EXHIBIT: REVOLUTIONARY FIGURES FROM AROUND THE DIASPORA

January 13th – May 25, 2024

The Black Power Exhibit: The Revolutionaries is curated by The Bolds and produced by the Southampton African American Museum in collaboration with Innovation Charter School in East Harlem.

The Black Power Exhibit: The Revolutionaries, is a provocative and educational exhibit that takes visitors on a journey of Black revolutionaries and revolutions from around the world in chronological order from the 14th century to present day.

In addition, a group of High School students from Innovation Charter School in East Harlem will be showcasing their artistic vision of Black Superheroes. Accompanying their artwork will be a written essay about their Superhero’s name, powers and how they use their abilities to unite, support and uplift the Black community worldwide.

Curators Frank Bold and Kilsi Rodriguez Bold are the founders of Bold Art Society, whose mission is to bridge the gap between students and potential careers in the arts. They provide high school and college students with professional opportunities in the arts.

Kilsi Rodriguez Bold has been a high school teacher for over 10 years teaching Entrepreneurship and Science. She was awarded “Teacher of the Year” in 2022 by the NYC Department of Education for her instruction in Career in Technical Education. She is the Director of Curriculum and Special Events for Bold Art Society.

Frank Bold is the Executive Director and seasoned playwright, producer, curator and educator in Harlem NYC. He currently teaches the Bold Art Society High School program at Innovation High School.

The exhibit will feature interactive activities so visitors can immerse themselves in the artwork while learning about history not often taught in schools. There will also be special programming throughout the duration of the exhibit.

Each Artist was specifically selected because of their unique styles and personal connection to the artwork.

August 5 – November 8, 2023

Tariku Shiferaw

Making Space: One of These Black Boys

The curator of the exhibition, Storm Ascher, writes: “Southampton African American Museum is the perfect container for Making Space: One of These Black Boys a solo exhibition by the visionary Ethiopian-American artist Tariku Shiferaw—who is exhibiting for the first time at the historic barbershop turned museum. Born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, raised in Los Angeles, CA, and currently based in New York, Shiferaw’s experience of cultures informs his multifaceted reference points in his work as an abstract artist. Shiferaw invites us on a journey through the realm of mark-making and its profound significance within society and art history.

Making Space: One of These Black Boys challenges us to question the prevailing notion of who possesses the authority to make marks and shape narratives. Shiferaw’s deliberate gestures serve as a powerful counter to the systemic erasure that has long plagued our history. In this series, the artist not only engages with the recorded history of painting but also prompts us to deeply consider the nature of our society and its functioning, in both the physical and metaphysical.”

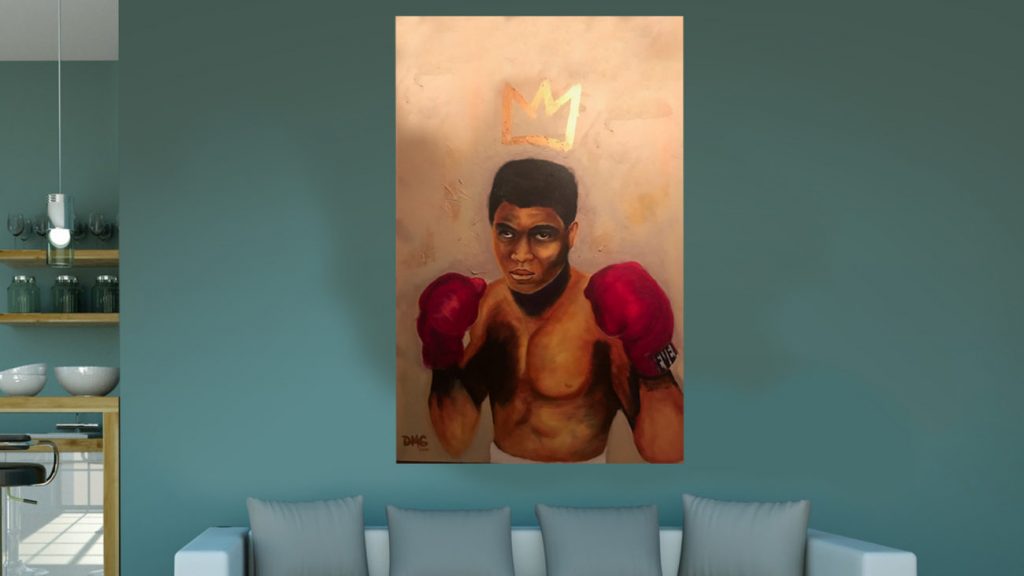

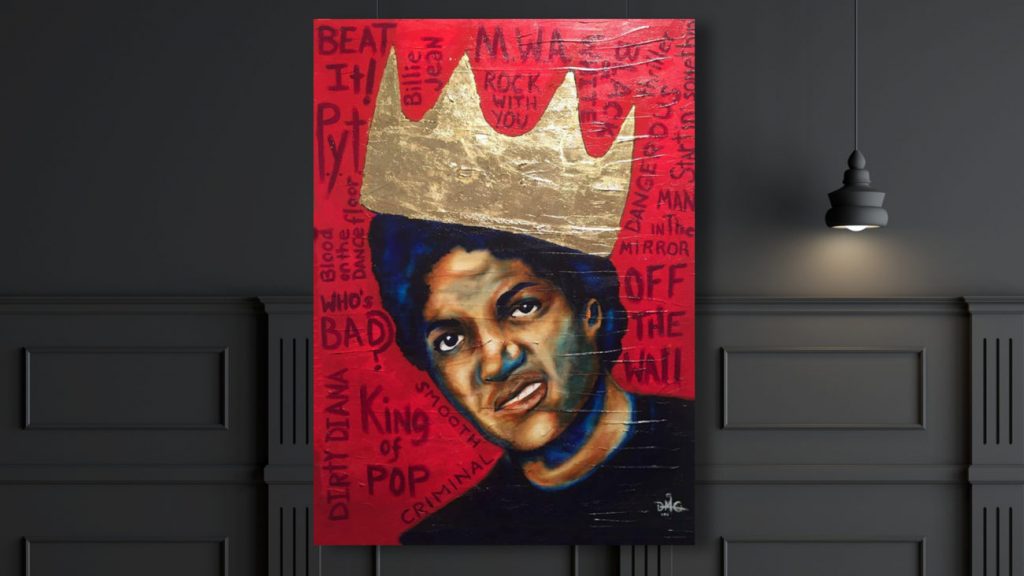

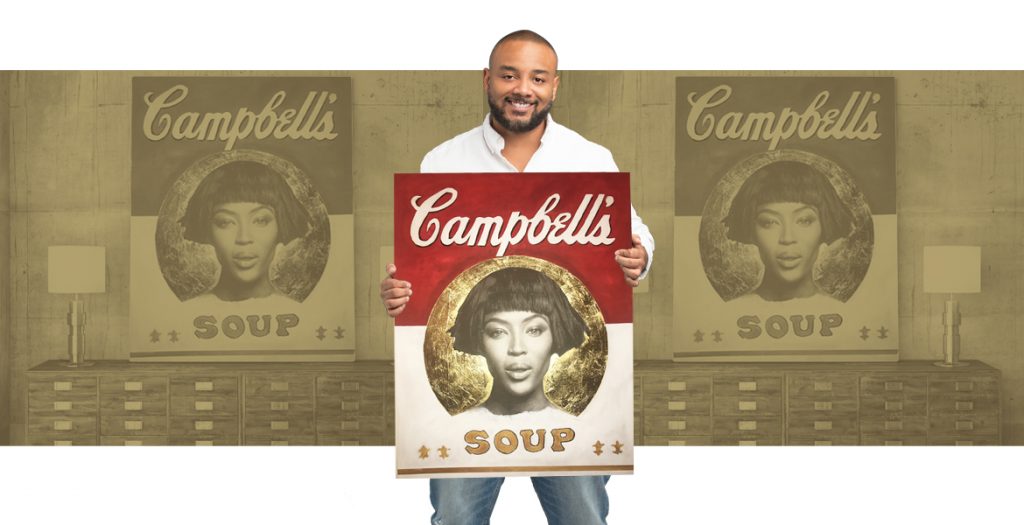

Artist Demarcus McGaughey: "KindRED"

Demarcus McGaughey was doing a residency at Ma’s House on the Shinnecock Reservation in Southampton and was encouraged to visit the Southampton African American Museum (SAAM) last summer.

He was eager to learn about the BIPOC community and especially the Black community that he did not know or think existed in Southampton (aka The Hamptons). After spending a few hours with Demarcus we felt a connection with the importance of preserving family history.

So Demarcus will be our 2023 Opening Art Exhibition entitled “ Kindred”. This exhibition will featured portraits of his family legacy which captured and align with our mission:

To promote an understanding and appreciation of African American culture by creating programs that will preserve the past, encourage learning and enhance the life of the community. SAAM will research and collect local history, produce media events, create exhibitions and community celebrations.

“Kindred” is multi-media artist Demarcus McGaughey’s most intimate and revealing series of work yet. One might describe it as his “long walk home.” Reflective and poignant, it comprises a multitude of timeless reminders of family moments. “Kindred” honors the sometimes-forgotten ancestry of Black Americans while acknowledging the cultural contribution of his family beyond enslavement.

The series comprises over 40 mixed media pieces exploring memory, identity, and spirituality and are inspired by his rediscovery of family photographs and cherished stories. These images reacquainted Demarcus with his history and reaffirmed for him the importance of understanding the impact of his family’s existence in the American south for more than five generations.

“While creating the work for ‘Kindred,’ I transported myself to a time where the appreciation of tangible items held a weight much heavier than present day,” he says. In a world where digital content is king, Demarcus honors his family’s legacy by way of family photo albums, boxes of snapshots, and generations of memorable stories. The work informs his ability to take his artistry and aesthetic to new heights.

“This is what I’m made of,” he says. “A tribe of ancestral family, friends, entrepreneurs, believers, and givers who transformed their lives through faith, familial bonds, love, hard work, fearlessness, and song. My goal was to reclaim their personhood in a society that challenged their very rite to fully exist.” The works are a canonization of his ancestors as symbols of divinity and triumph; spiritual icons ever watching over those who acknowledge that they were here.

With paper collage, inherited fabrics that belonged to his grandmother, acrylic, and resin on canvas, you are invited to view a collection of memories and documentation of culture through Demarcus’ eyes. The choice of dimensions for these generational treasures and keepsakes are small with the artist’s desire to share with you weathered yet impressive family tales. His hope is that you will see you and your family in his.

Demarcus McGaughey, a Texas native and New York-based mixed media artist, passionately captures the beauty, strength, and vibrancy of people of color.

Inspired by his mother as a child, he sharpened his artistic talents by coloring within the lines of her tracings. Eventually, he tapped into his storehouse of magic that pushed him to color outside the lines and chart an artistic path of his own.

McGaughey specializes in a style that combines painting, photography, mixed media, and graphic design. This elixir of artistic elements stems from his fruitful stint in corporate advertising and graphic design. Post undergrad, he licensed his time and talents to ad agencies and corporations as a freelance designer. Since then, he’s developed a mastery of graphics, product development, branding, and brand coaching.

In the early days of his career, he found graphics to be the ideal catalyst to tell stories for other people. But it was through painting that he discovered an avenue to tell stories, his way. His vibrant portraits capture elements of his world travels, his family, and his community. Each painting, a love letter to the world, declaring, “I see you and I hear you.” Behind his art, resides a lifelong fascination with human psychology. McGaughey has always been intrigued by the mind, especially the stories people tell themselves.

As a result, in his art he assumes a narrator role—telling heroic stories of his subject’s self-actualization and self-determination. As a certified life coach, he passionately empowers his coaching community that life is what you create it to be. His portraiture work reveals triumphant tales of African American subjects who have manifested their destiny with a particular focus on the eyes, the window to the soul. McGaughey also pays homage to cultural influences with elements of pop art, mass media, comic books, and advertising in his pieces. Inspired by Barkley Hendricks, who famously painted Black people in all their coolness, McGaughey portrays his people in a larger-than-life display.

Drawing inspiration from Andy Warhol’s acclaimed artistry in pop art and advertising along with Kehinde Wiley’s massive masterpieces, McGaughey’s work exudes an undeniable flow. Throughout his 20-year art career, McGaughey has worked with prestigious brands and organizations, including Beyoncé Knowles Carter and beverage giant Dr. Pepper. His work has been highlighted in numerous magazines and galleries stateside in New York and Texas, and globally in Spain. He has completed art residencies with Mas el sigols in Barcelona, Nfinit Foundation Arts Residency in Brooklyn, and Art Crawl Harlem in New York. He has the distinct honor of being selected as a 2021 Artist-In-Residence at Chateau Orquevaux in France. Through his captivating lens, Demarcus McGaughey hopes to continue to inform inspiring stories of Black triumph.

Digital Tapestry Experience "Soft Launch"

Digital Tapestry, a historically focused virtual and augmented reality experience which uses a cell phone app to bring certain aspects of a museum to life in a new way for visitors and even those who cannot be at the museum in person.

The technology works off an actual tapestry that is one of the centerpieces of the SAAM, a work of art created by David Bunn Martine of the Shinnecock Nation.

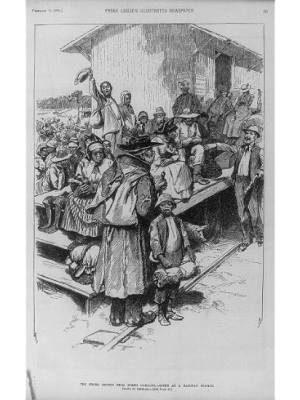

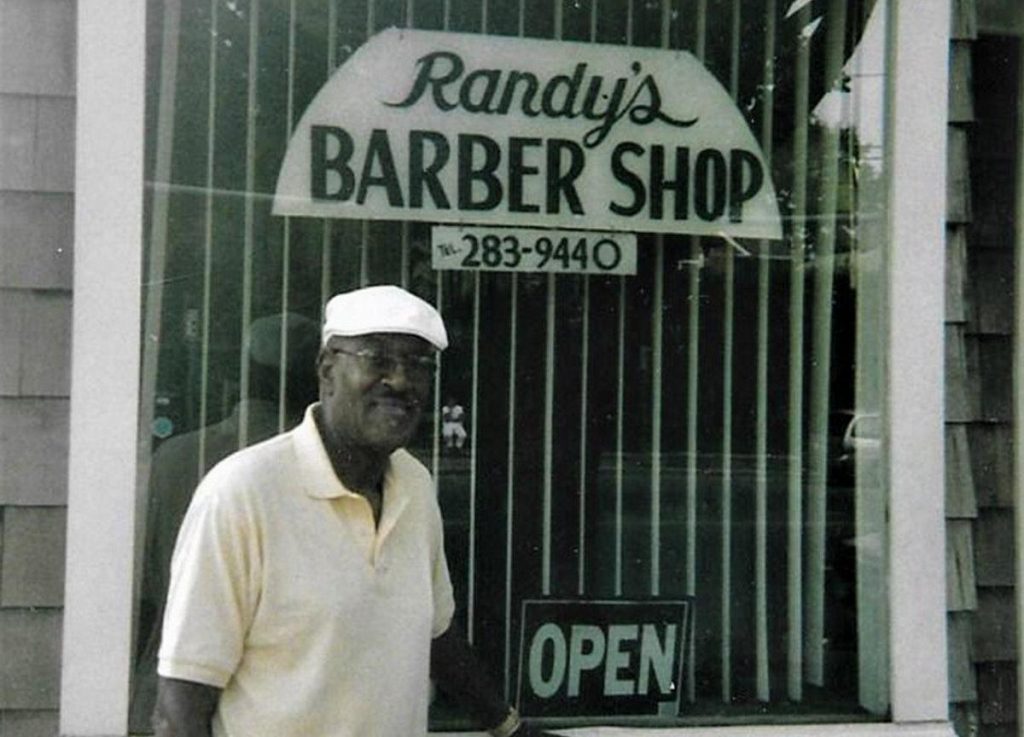

It depicts various scenes representative of Black history in Southampton, including a likeness of Concer, images of African Americans who left their homes in the South in droves to come work on farms in the North — including on eastern Long Island — as part of the Great Migration of the middle of the 20th century, and depictions of both juke joints and Randy’s Barber Shop, which was housed where the museum now stands in Southampton Village.

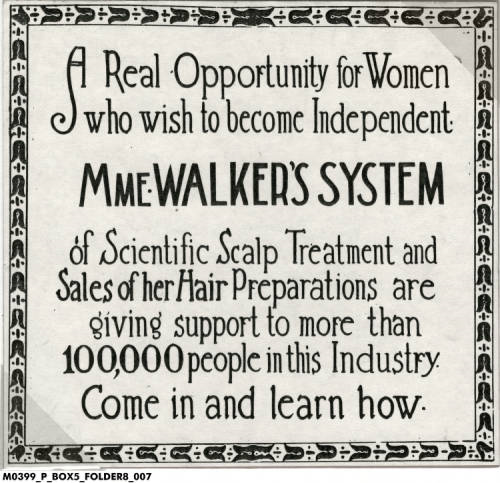

Black Barber & Beauty Shops in America

The Southampton African American Museum is housed in a former Black barber shop and beauty parlor, which doubled as a juke joint. Built in the 1940s by Emanuel Seymore, it was one of the region’s leading Black-owned businesses and a vibrant gathering place for Black Southamptonites for over a half century. Since the 1800s, Black barber shops and beauty parlors have similarly created economic opportunities, fostered civic engagement, and sustained communities throughout the United States. This exhibition illuminates their historical significance and introduces some of the individuals who worked, patronized, and socialized at this popular establishment.

Until the mid-20th century, barbering and hairdressing were among the few careers open to African Americans that created pathways to entrepreneurship and financial independence. In towns and cities across the nation, Black-owned barber and beauty shops provided essential services and skilled jobs, and contributed to the local tax base. In many neighborhoods, they still provide a welcoming environment where people can relax, exchange information, discuss problems and current issues, and participate in political activities. A remarkable number of prominent African Americans built illustrious careers in the haircare industry or used it as a stepping stone to other ventures. Many more relied on their local barber or beauty shop as a nurturing space through the various chapters of their lives.

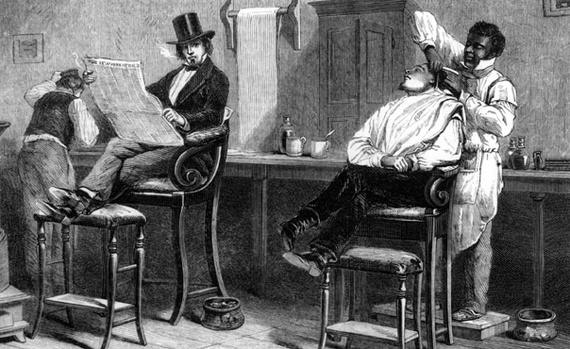

Brotherhood of Barbers

Black barbers, free and enslaved, were among the first craftspeople in early America. For those in bondage, barbering skills enhanced their value within the slave system and, in some cases, provided the means to secure their freedom. By virtue of their shared experiences and occupational identity, Black barbers regarded themselves as belonging to an informal brotherhood, whose members–despite friendly competition–looked out for each other, as well as their families, friends, and neighbors, and dutifully passed on their knowledge and skills to younger men. Given their vital role, Black barbers were widely known, well connected, and respected in many communities. They often took on leadership positions, using their public platform to advance their fellow African Americans, especially those still in bondage. By the early 1800s, Black men nearly monopolized the barbering trade in the United States. While most worked in established barber shops, an increasing number, after building up savings and loyal clienteles, launched their own businesses. Whether in the Deep South or the segregated North, however, Black-owned barber shops often survived only by catering to exclusively white clienteles. As the lives and livelihoods of these ‘captive capitalists’ depended on shaving white men, as historian Quincy Mills explains, “barbering symbolized both the possibilities and limits of freedom for African Americans in the antebellum period.”

Prior to the Civil War, Black barbers actively opposed slavery in the United States. After intensive agitation by an interracial coalition, New York State passed the “Act for Gradual Abolition” in 1799, which slowly ended slavery in the state by 1827. But since slavery persisted elsewhere, they redoubled their efforts. In Boston, Peter Howard’s barber shop served as a station on the Underground Railroad.

In Philadelphia, barber Joseph Cassey, despite operating a segregated shop, was the first local agent for The Liberator, the leading anti-slavery newspaper, and barber Frederick Hinton circulated antislavery petitions, participated in the Anti-Slavery Society’s activities, and demanded voting rights for Black men in Pennsylvania. In response, white supremacist mobs targeted their homes, businesses, and meeting places, including burning down Pennsylvania Hall, headquarters of the Anti-Slavery Society, in 1838.

To escape growing violence, Hinton and his peers debated moving to Trinidad, Haiti, or other places where slavery had been abolished. Like the vast majority of African Americans, however, they ultimately refused to be driven out of the land of their birth. When the Civil War erupted, thousands enlisted in the Union Army, including many barbers who took up arms as well as scissors. Not coincidentally, several of the nation’s first Black Congressmen made their start earlier as barbers.

During Reconstruction and beyond, Black barbers, while continuing to demand equal rights as citizens, enjoyed a new level of mobility and prosperity. Many found work in elegant hotels, department stores, and aboard luxury railcars and ocean liners. In large cities, they staffed palatial “tonsorial parlors” that competed for affluent customers. Some of the most opulent parlors were Black owned but still segregated. With growing social status and investment capital, the most successful barbers diversified into manufacturing, real estate, and other ventures. Many pursued cultural and philanthropic interests as well. They also continued to bring more apprentices and journeymen into the brotherhood of barbers.

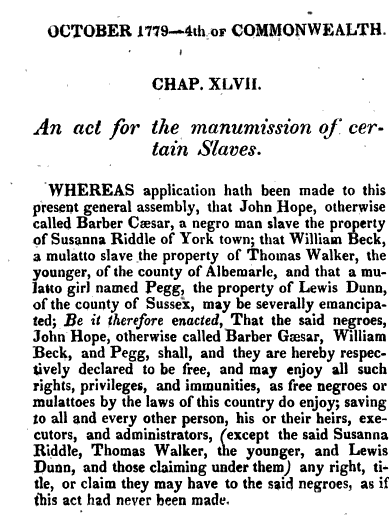

John “Caesar” Hope

John “Caesar” Hope (c. 1733-1810) was one of the most successful barbers in early America. Born in West Africa, he was only ten in 1743 when he was captured and sold into slavery. When he arrived in colonial Virginia, his new owner renamed him Ceasar and put him to work in his barber shop. Through three successive owners, Caesar operated the business with considerable autonomy. During the American Revolution, he rejected Governor Dunmore’s offer to free enslaved men who fought on the British side. According to the Virginia Gazette, Caesar stated that if the governor really “intended slaves to be free, he ought to set his own free.” In 1779, Caesar’s decision paid off when his owner’s widow successfully petitioned the Virginia Assembly for his freedom, with endorsements from over thirty of his white male customers. To celebrate, he adopted a new name–John Hope. After the war, he set up his own business, earning enough to buy his wife and son out of bondage. When he died in 1810, his wife inherited his property and was later able to buy the freedom of their youngest daughter as well.

Law passed by Virginia’s State Assembly, freeing John “Caesar” Hope and three others, October 1779.

William Lee depicted in Edmund Savage’s “The Washington Family,” 1798.

William “Billy” Lee

William “Billy” Lee (c. 1750-1810) served as the personal valet and barber to George Washington. Born into slavery, Lee arrived at Mount Vernon in 1768 after Washington bought him for £61. Every day for over 20 years, Lee shaved Washington’s face, cut his hair, styled and powdered his wig, cared for his clothing, and helped him dress, among myriad other tasks. During the American Revolution, Lee accompanied Washington on military campaigns, serving as a trusted messenger and attending to the general’s horse and arms. As a reward for his loyalty and war-time service, Lee was freed in Washington’s Will–the only one of the former president’s slaves immediately freed upon his death.

PIERRE AND JULIETTE TOUSSAINT

Pierre and Juliette Toussaint, by Anthony Meucci, ca. 1825. Courtesy of New-York Historical Society.

Pierre Toussaint (ca. 1781-1853) was born into slavery in St. Domingue but came to New York City in 1787, on the eve of the Haitian Revolution. After securing his freedom, he took the surname “Toussaint” in honor of the Haitian hero, Toussaint Louverture. Although initially trained as a house servant, Pierre learned to read and write from his grandmother. To escape growing political tensions, Pierre, his sister, aunt, and two other enslaved servants, accompanied their enslaver’s son to New York City. Apprenticed to a local hairdresser, Pierre, then in his early twenties, proved a quick learner and began providing services to customers in the comfort of their own homes. Although still enslaved and permitted to keep only a portion of his earnings, his client list soon included many of the city’s wealthiest women. In 1807, Pierre gained his freedom upon the death of his enslaver’s wife, after having financially supported her during her long exile. Four years later, he married Juliette, after buying her freedom, and they later adopted his orphaned niece Euphémie. Consistent with their religious beliefs, they assisted anyone in need, regardless of their race or circumstances. They also organized an employment bureau, a credit union, a settlement agency to assist Haitian refugees, and the city’s first Catholic school for Black children. Pierre won many hearts when he bravely nursed the ill during a devastating cholera epidemic. Urged by friends to retire and enjoy his considerable wealth, Pierre responded, “I have enough for myself, but if I stop working I have not enough for others.” After his death, his body was reinterred in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in honor of his good works; once refused entry there because of his race, he was laid to rest beneath the main altar, an area generally reserved for bishops. In 1996, in a step towards sainthood, Pope John Paul II declared Pierre Toussaint to be Venerable.

1772 Runaway Barber, David, Gazette Williamsburg, Virginia Nov 12 1772

1795 Runaway Barber, Pierce, Oct 22 1795 Aurora General Advertiser Philly

1813 Sale Barber, Smart Boy, Charleston Daily Courier Nov 29 1813

1774 Barber Runaway Mulatto Boy, PA Gazette Oct 12 1774

1817 Sale Cook and Barber Charleston Daily Courier July 25 1817

1840 For Sale House Slave Barber Charleston Mercury Jan 22 1840

1837 For Sale Gentleman Servant barber Charleston Daily Courier Jan 25 1837

1855 Runaway Hairdresser Susan Times Picayune New Orleans March 21 1855

1833 Runaway Barber from Hotel Natl Banner / Daily Advertiser Nashville Sept 5 1833

1830 Runaway Barber Thomas, US Gazette Philly Sept 10 1830

1825 Runaway barber Dick Natchez Gazette Miss April 2 1825

1822 Runaway barber Alexander Knoxville Register TN Nov 26 1822Examples of enslaved barbers and hairdressers for sale and self-liberating (to label & arrange chronologically)

John Bathan Vashon

In the 1830s, John Bathan Vashon (1792-1853) transformed his Pittsburgh barber shop into a hub of antislavery activities. Although the child of an enslaved woman named Fanny and her enslaver’s son, Vashon was born free in Norfolk, Virginia. During the War of 1812, he served as a sailor aboard the U.S.S. Revenge and was captured by the British off the coast of Brazil and held prisoner for two years. Upon his return to Virginia, he married Anne Smith and relocated to Pittsburgh, where he established an up-scale barber shop that made him one of the city’s wealthiest residents. While serving only white customers by day, Vashon’s barber shop was a station on the Underground Railroad by night. In addition to hosting meetings of the Pittsburgh Anti-Slavery Society in his home, Vashon was a trustee of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, co-founder of the Pittsburgh African Education Society, and a financial backer of the antislavery newspaper, The Liberator.

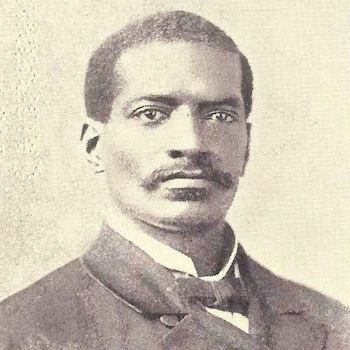

Joseph Hayne Rainey (1832-1887) was born to enslaved parents in South Carolina. His father, a barber who was permitted to keep some of his earnings, saved enough money to purchase his family’s freedom. Barred from attending school, Joseph Rainey never received a formal education. Instead, he learned his father’s trade and worked as a barber at an exclusive Charleston hotel in the 1850s. During the Civil War, Rainey and his family escaped to Bermuda, where slavery had been abolished, and established a successful barber shop and dress store. Upon their return to Charleston after the war, Rainey became the first African American elected to the U.S. House of Representative for South Carolina, a position he held for eight years, making him the longest serving Black Congressman during Reconstruction. During his term in office, Rainey worked to pass civil rights legislation, fund public schools, and guarantee equal protection under the law. In response to white supremacist terrorism in the South, Rainey also endorsed the Enforcement Acts, which enabled the federal government to expand its authority over the states in order to dismantle the Ku Klux Klan.

Hiram Rhodes Revels (1822-1901) was born free in Fayetteville, North Carolina, apprenticed in his brother’s barber shop, attended Knox College, and later became a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. In the Civil War, he served as a chaplain and helped organize colored regiments. During Reconstruction, he was the first African American elected to the U.S. Senate, representing Mississippi from 1870 to 1873, completing an unexpired term. He went on to serve as Mississippi’s secretary of state. By the 1890s, he had acquired a sizable plantation near Natchez.

Alonzo Herndon (1858-1927)

Alonzo Herndon (1858-1927) was born into slavery in Georgia. His mother, Sophenie, was an enslaved woman, and his father was a plantation owner. Only seven years old when the Civil War ended, Alonzon labored with his sharecropper family, leaving home at age 20 with only $11 and one year of schooling. After learning to cut hair, he was hired by William Hutchins, one of the few free Blacks who owned a barber shop in pre-war Atlanta. Within six months, Herndon became his business partner, then acquired his own shop, and eventually built a whole chain of barber shops. Known as the “Crystal Palace,” his flagship location in down-town Atlanta boasted chandeliers, gilt-framed mirrors, and marble fixtures. As dictated by the era’s racial divisions, however, his establishments served white customers only. As his fortunes improved, Herndon devoted considerable resources to funding Black schools, churches, and orphanages. To encourage mutual support among his fellow barbers, he founded the Atlanta Barbers Advancement Association in 1876, which grew into the national American Barbers Advancement Association. He was also on the vanguard of the early Civil Rights Movement. In 1900, he attended the National Negro Business League’s inaugural meeting, convened by Booker T. Washington. Five years later, he joined the Niagara Movement, a precursor of the NAACP, founded by W.E.B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells, and other prominent Black activists. Resentful of Herndon’s success, Atlanta’s white barbers lobbied for city regulations designed to undermine his business. Undeterred, he expanded from barber shops into real estate, acquiring over 100 properties, and in 1905 founded the Atlanta Life Insurance Company. That same year, as white politicians tried to disenfranchise Black voters, racial tensions boiled over, and Atlanta exploded in violence. During two days of terror, white rioters killed at least 25 African Americans (and possibly as many as 40) and attacked Black-owned homes and businesses. After smashing the Crystal Palace’s windows, the angry mob, failing to capture Herndon, murdered the Black barbers in a nearby shop. Similar incidents of racially-motivated terrorism repeatedly occurred during the Jim Crow era, leading many Black barbers to move North. Even after that horrific event, however, Herndon refused to be driven out of business or out of Georgia. He eventually became one of first Black millionaires in the United States and devoted much of his wealth to improving conditions for African Americans.

Increasingly, African Americans, especially in the North, sought to challenge racial inequality in all its insidious forms. To leverage their economic power as consumers, they patronized Black-owned businesses whenever possible and denounced those with discriminatory policies, ushering in a new generation of barbers who moved to African American neighborhoods where they could serve more diverse clienteles. Barber shops that remained “whites-only” could now expect protestors outside their doors. In 1886, for example, the New York Freeman reported that in Boston after a local Black barber “refused, point blank, to accommodate another respectable colored man,” outraged young men called for a boycott of his business. In the same issue, another barber announced the grand opening of his “equal rights shop.”

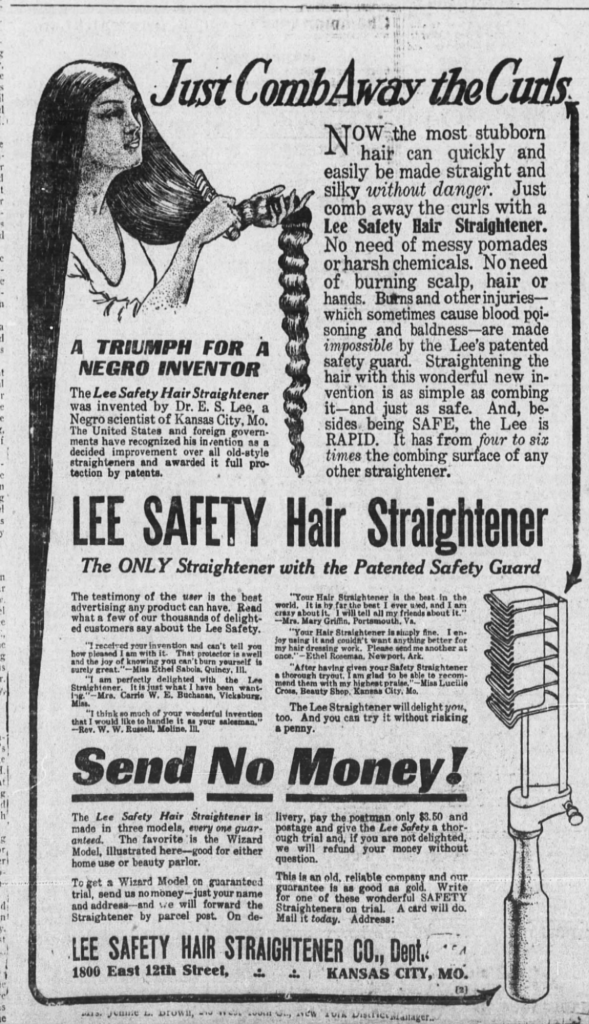

During the early 20th century, Black barbers also became inventors, developing new tools and products. In moving from the service sector to manufacturing, they opened new opportunities for other African Americans and remained at the forefront of efforts to promote Black economic advancement and civil rights. In 1905, W.E.B. Dubois invited 29 prominent black men, including barber Alonzo Herndon, to meet at Niagara Falls in Canada. They demanded the end to segregation and appealed for better schools, health, and housing for African Americans. What emerged from this meeting became known as the Niagara Movement, which attracted 400 members and emphasized Black self determination. Eventually, it was superseded by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, thousands of African Americans moved to the North to escape the overt racism and growing violence of the Jim Crow South. This “Great Migration” brought a surge of newcomers to New York City, especially from Virginia and the Carolinas, most of whom found work in factories, transportation, hotels, and other urban businesses. At the same time, the city also saw a growing influx of Irish, German, and Italian immigrants, including many trained barbers.

In response to increasing competition, barber shop owners tried to attract more customers by establishing professional organizations dedicated to improving training, setting quality standards, and lobbying for advantageous state regulations and licensing requirements. Apprentice and journeymen barbers, like other wage workers, established their own unions to negotiate better pay and labor conditions. Most of these organizing efforts, however, fractured along racial, ethnic, and gender lines. White barbers, for example, established new trade organizations and unions that excluded people of color. They, in turn, founded their own professional organizations and labor unions. By the end of World War I, the American Barbers Advancement Association, founded by Alonzo Herndon, was the largest network of barbers in the country.

Walter Sammons (1890-1973)

Walter Sammon’s Hot Comb design (U.S. Patent #1,362,823); Ad for Dr. E. S. Lee’s “Safety Hair Straightener,” Feb. 25, 1925, New York Age, one of many competing hot combs.

In his patent application, Sammons declared that existing “hair-straightening or kink-removing combs. . . have resulted in irreparable damage to the hair and not infrequently injury to the hands of the user. . . . [My] invention consists essentially in housing within the body of the comb proper, a thermometer . . . [that] can be heated. . . to the requisite degree and used on extremely curly or kinky hair to straighten out the same without . . . burning or damage by simply passing the teeth of the comb through the hair.”

Walter Sammons (1890-1973), a Philadelphia inventor, is most remembered for his 1920 patent for a hot comb. Since his design was one of many developed by African American inventors, male and female, in the early 20th century, the need for technical improvement was clear. Many Black women recall the smell of scorched hair and occasional burns while having their hair styled. Frenchman Marcel Grateau is credited with inventing the first hot comb in the late 1800s, which was initially used by white women in Europe and America. Sammons’s hot comb, designed to smooth textured hair when heated and drawn through from roots to tips, was marketed to African Americans at a time when natural hair was considered less refined than processed hair.

Then as now, people styled their hair in different ways for complex personal and social reasons. For some women, hair-straightening “marked the passage to adulthood, from the childhood tradition of wearing braids. . . . For other women, having straight hair aided with assimilating into a society where having long, straight hair was valued as ‘good hair,’ an asset that many perceived as more attractive . . . [and thus] elevating a woman’s personal, social, and economic status” To create the prevalent styles of the day, African Americans modified their appearance with the help of technology and various hair products. Even then, however, some rejected the notion of enduring pain just to meet other’s arbitrary beauty standards.

Hunter C. Haynes (1867–1918)

Hunter C. Haynes (1867–1918), the son of a formerly enslaved laborer and seamstress, began working at age 10 as a shoeshine boy at a large hotel in Selma, Alabama. When he was 14, Haynes apprenticed as a barber for 15 months. His new skills enabled him to travel all over the country, finding work in different cities along the way. Around 1890, he returned to Selma and opened his own barber shop. Recognizing the need to improve the sharpening of razors, he invented a leather strop, patented in 1920, which immediately attracted customers. Since opportunities for a Black manufacturer were limited in the Jim Crow South, Haynes moved to Chicago, establishing an integrated barber shop, a factory, and a mail-order business. He later built a larger New York-based company, in partnership with Gottlieb and Hammesfaber, a German steel company. Thanks to his financial success, Haynes was then able to pursue his true passion–making movies! After serving as a producer for a white-owned company, he launched Haynes Photoplay Company which featured Black movie stars.

During his career, Haynes, worked closely with the National Negro Business League (NNBL), founded by Booker T. Washington in 1900 to promote Black economic prosperity. Established during the nadir of race relations, when Blacks were denied the vote in the South and deprived of virtually all Reconstruction-era gains, the NNBL organized hundreds of chapters to encourage collaboration among Black businesses, including barber shops and beauty parlors. At its first meeting, Boston native Gilbert C. Harris spoke on the topic “Work in Hair,” and T. H. Thomas of Galveston, Texas, spoke on “Barbering.” At the NNBL’s 15th Anniversary Convention, Mary L. Johnson of Boston, J. R. Barreau of New Bedford, Massachusetts, and G. A. Coleman of Washington, D.C., gave a joint talk entitled “The Beauty Parlor Business.” These annual meetings provided forums for mutual support where attendees could share success stories, form joint ventures, and discuss effective marketing strategies to reach Black customers. One of the featured speakers in 1905 was H. C. Haynes, who traveled from Chicago to New York to present on “Manufacturing Razor Strops.”

Ad for “Haynes Razor Strop Co.” in The Crisis, May 1912.

Beauty is Our Business

After the Civil War, African American women increasingly found opportunities in the hair care industry. Years of experience caring for their own and their loved ones’ hair gave them highly marketable skills. Some formerly enslaved women, such as lady’s maids, also had specialized training in creating the elaborate hairstyles worn by elite women. A few women even broke into the male-dominated barbering trade, especially those with male relations in the business. Compared with most jobs then open to women outside the home, hairdressing offered a viable livelihood, which was key to personal autonomy and financial security, especially for those who were single, widowed, or raising children on their own.

Until the 1910s, most independent hairdressers kept overhead low by providing services in their homes. Determined to professionalize on par with their male counterparts, Black women hair stylists began setting up separate beauty parlors, technical schools, and trade groups, organizing the National Beauty Culturists’ League (NBCL) in 1919, which established industry standards, offered training sessions, and lobbied for advantageous state regulations.

In the 1920s, beauty shops proliferated with the Jazz-Age fad for “bobbed” hair. When young flappers started requesting short haircuts, male barbers were so shocked that some refused them service. Beauty parlors, meanwhile, vied for women’s business by advertising the latest fashions and treatments. They also served as centers of community life where, according to a 1926 article in the Afro American, one could learn the latest news, “listen to the choicest bits of scandal, hear the private life of one’s neighbor’s discussed, and collect opinions of all and sundry on the events of the day.”

Enterprising Black women were also at the forefront of developing commercial hair and skincare products for African Americans. These female pioneers “believed that for African American women, appearance and grooming represented more than personal style, but could also indicate their class and social standing, and that improving hair health could also have a positive effect on their lives.” Facing a tidal wave of mass marketing that reified whiteness–especially light skin and straight hair–they were determined to help women thrive in spite of social pressures to meet racist beauty standards. As leaders, mobilizers, and financial contributors, beauticians were very involved in their communities and the larger political arena. At the NBCL’s national convention in 1957, Martin Luther King acknowledged their contributions in his speech, “The Role of Beauticians in the Contemporary Struggle for Freedom.” Thanks to their vision, determination, and business savvy, they soon controlled a large slice of this lucrative sector of the beauty industry–an extraordinary accomplishment for Black women in a segregated and highly sexist society.

Christiana Babcock Bannister (1819-1902)

Christiana Babcock Bannister (1819-1902) was born in North Kingstown, Rhode Island, to African American and Narragansett Indian parents. She was a descendant of enslaved Africans who worked the plantations of South County, Rhode Island, during the 18th century. As a young woman, Christiana moved to Boston and became a hairdresser, wigmaker, and self-styled “hair doctress.” By the 1850s, she owned and operated several salons, where she sold her own hair products. In 1853, she met Edward Bannister when he applied for work as a barber in her Boston salon.

After their marriage, Christiana and Edward Bannister opened their hair salons as meeting places for abolitionists and stations on the Underground Railroad. During the Civil War, Christiana organized fundraisers to aid Black regiments that served for a year and a half without pay rather than accept lower wages than white soldiers. After the war, the Bannisters moved their business to Providence, where Christiana continued her charitable works, including founding a retirement home for Black women left homeless when they could no longer work. Thanks in large measure to her financial and emotional support, Edward Bannister became one of Rhode Island’s most famous artists. In honor of her humanitarian efforts, a bronze bust of Christiana, based on this portrait, was dedicated at the Rhode Island State House in 2002.

Annie Turnbo Malone (1869-1957)

Annie Turnbo Malone (1869-1957) was the child of formerly enslaved parents. During the Civil War, her father went to fight for the Union while her mother and siblings escaped to freedom in Illinois, where Annie was later born, the 10th of 11 children. Orphaned at a young age and forced to leave high school early, she developed a passion for haircare by styling her sisters’ hair. After much experimentation, Malone developed her own product line. After giving demonstrations of her “Wonderful Hair Grower” in the streets and selling directly to customers, she soon couldn’t keep up with demand. In 1918, she built a large factory and founded Poro College (named after a secret West African society that celebrated physical and spiritual well-being) in an affluent Black neighborhood in St. Louis. While her company employed hundreds of African Americans, especially women, as workers and sales agents, the college offered training in the care and styling of Black hair and provided a meeting place for organizations, like the National Negro Business League, that were denied access to most public spaces. By the 1920s, her products were sold throughout the United States, Africa, South America, and the Caribbean. As one of America’s wealthiest women and one of its first Black millionaires, Malone donated large sums to local and national philanthropic efforts. By 1930, however, her fortunes declined due to a divorce and the ensuing Great Depression, although her company managed to survive.

Sarah Spencer Washington (1889-1953)

Sarah Spencer Washington (1889-1953) was born in Virginia and studied chemistry at Columbia University. Although her parents wanted her to become a school teacher, she opened a one-room beauty parlor in 1913 in Atlantic City. Drawing on her chemistry background, she started inventing new hair products, even securing a patent for an innovative hair straightening system. While still styling hair by day and selling her products in the evenings, Washington founded Apex Hair Company in 1919, manufacturing everything from pressing oils, hot combs, and hair pomades to perfumes, creams, and lipsticks. By the mid-1930s, her company was New Jersey’s largest Black-owned business, with over 500 employees and an estimated 45,000 global sales representatives. In addition, she established laboratories, drug stores, a publishing company, and Apex Beauty College, which opened 11 locations in the U.S. and overseas. At the 1939 World’s Fair, Sarah Washington received a medal as one of the nation’s “Most Distinguished Businesswomen.”An out-spoken champion of civil rights, she filed numerous lawsuits and took direct action to challenge segregation in Atlantic City. When a local restaurant refused to admit Blacks, for example, she rented out its entire dining room until the owner finally agreed to change his policy.

Estelle Brown Hamilton (1883-1933)

Estelle Brown Hamilton (1883-1933) was born in Savannah, Georgia. Widowed at age 27, she moved to New York where she trained as a beautician and set up a one-room shop on 133th Street in Harlem. After almost immediate success, she acquired a larger premises but faced growing competition. By 1921, Harlem had 103 hairdressers and 51 barbers; two years later, the neighborhood had 161 beauty parlors, more than any other business. Seeing power in numbers, Hamilton encouraged cooperation among them, even serving as the first president of the National Beauty Culturists’ League.

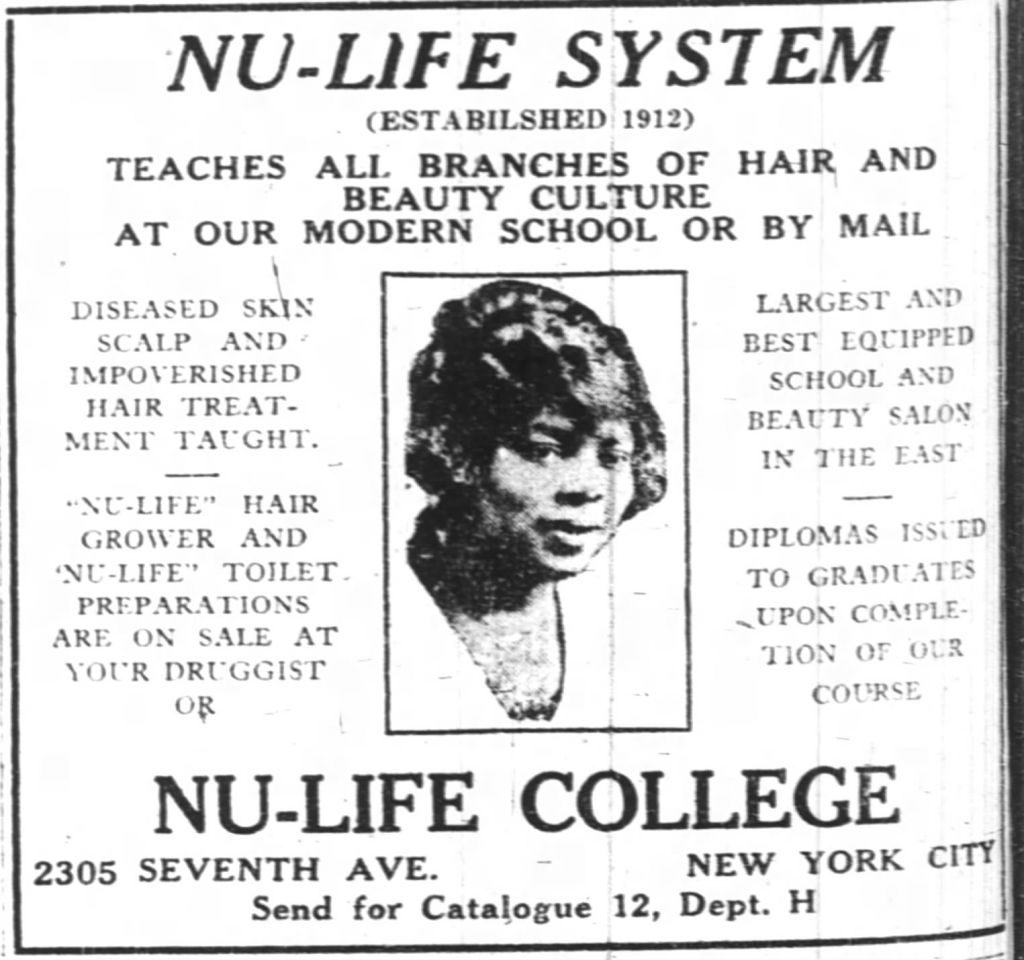

At the same time, Hamilton found a new niche in manufacturing hair products based on her own secret formulas. After securing her first patent in 1916 for a hair pomade, she founded the Nu-Life Beauty College, which educated young women in the emerging science and culture of Black hair and skin care. Before long, Nu-Life graduates all over the country were using her techniques and selling her products. Hamilton also organized numerous fundraising events to benefit the people of Harlem, including an initiative to establish a retirement home for the elderly. After suffering a burn in her laboratory at the beginning of the Great Depression, she retired to Long Island in 1931.

Madame C. J. Walker (1867-1919)

Madame C. J. Walker (1867-1919), born Sarah Breedlove, was the daughter of formerly enslaved sharecroppers on a Louisiana plantation. One of six children, she was orphaned at age seven and went to live with her older sister. To escape the cotton fields, she married at age 14. After her husband died, she moved with their two-year-old daughter A’Leilia to St. Louis, where her four brothers were barbers. She initially worked as a laundress and cook, and became an active member of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1904, her life took a dramatic turn when, after a bout of hair loss, she became first a customer and then a sales agent for Annie Malone’s hair-growing products. After remarrying and taking her husband’s name, Madam C. J. Walker launched her own line of hair and skin care products. Thanks to brilliant marketing, she developed a thriving mail-order business. By 1910, when she built the Walker Manufacturing Company in Indianapolis, her name had become a nationally recognized brand.

Madame Walker built an empire on hair care and personal grooming products. Determined to support female empowerment, she trained innumerable young women at her beauty schools, many of whom became licensed sales agents or opened their own franchised salons. Walker-affiliated beauty parlors, schools, and sales outlets ultimately employed an estimated 40,000 men and women around the world. Madam Walker also became a generous philanthropist and a vocal advocate for African American concerns, contributing to educational institutions, the YMCA, the Tuskegee Institute, and the anti-lynching movement. At the National Association of Colored Women’s annual conference in 1918, the year before her death, Madam Walker urged the audience to take “the lead in every locality not only in operating a successful business, but in every movement in the interest of our colored citizenship.”

-

Post Card of Madam C. J. Walker’s factory, circa 1920. The postcard describes the factory as a “strictly fireproof structure . . . [of] steel, reinforced concrete, hydraulic press brick, white and polychrome terra cotta, fine imported marbles, birch and cypress wood, terrazzo floors, . . . [with] a $15,000 pipe organ, . . . and some of the world's finest machinery.”

Courtesy of the Indiana Historical Society.

Ad depicting Walker’s rise from a “slave cabin” to a mansion; Madam C. J. Walker, ca. 1912, at the wheel of her Model T. Ford, with her niece, bookkeeper, and factory manager; National Convention of Walker Beauticians, 1924, at Madame Walker’s mansion in Irvington, New York; Madame Walker with Booker T. Washington (center) and other dignitaries at dedication of the new YMCA in Indianapolis in 1913. Walker worked tirelessly to raise funds for it and personally donated over $1,000–a substantial sum at the time.

Courtesy of the Indiana Historical Society.

Walker instructors teaching hair care theory and demonstrating styling methods to beauty school students; advertisement recruiting women to become Walker sales agents, 1950s.

Courtesy of the Indiana Historical Society.

Marjorie Joyner (1896-1994)

Marjorie Joyner (1896-1994) grew up in Virginia, the granddaughter of an enslaved woman. In 1912, she moved to Chicago to study cosmetology with Madame Walker. After graduating, she opened a beauty parlor and served as a Walker sales agent. In 1919, after Madame Walker’s death, Joyner took over as the national supervisor of the Walker Beauty Colleges. A few years later, Joyner invented the first permanent wave machine, which made her well-known in her own right. At the time, African American women customarily straightened their hair using stove-heated curling irons, a slow process because only one iron could be used at a time. Joyner’s inspiration came to her one afternoon while making a pot roast in her kitchen. Observing the long thin rods used to hold the roast together in the oven, she realized that a similar system could be used to curl several sections of a person’s hair at once. After experimenting with actual pot roast rods and an old hair-dryer hood to develop a prototype, she patented her invention in 1928. Joyner’s “Permanent Waving Machine” was widely adopted by beauty parlors, black and white. Since the Walker Company retained the patent rights, however, Joyner made little money from her popular invention. Neverthless, she invested her energies in her church, community service, and the promotion of beauty trade organizations and schools. After retiring, Joyner returned to college, graduating at age 77.

Rose Morgan (1912-2008)

Rose Morgan (1912-2008) was born in rural Mississippi and grew up in Chicago, where she became a businesswoman at age 10, making and selling paper flowers to her neighbors. At age 12, she found her true calling when she started styling her friends’ hair. After leaving high school to work full-time, Morgan attended beauty school and secured her license. Developing her own hair-care techniques, she built a large clientele. In 1938, by a twist of fate, singer Ethel Waters visited Morgan’s shop while in Chicago and was so impressed that she invited the hairdresser to visit her in Manhattan. Enamoured by the glamourous city, Morgan moved to Manhattan and rented a booth for $10 per week in an uptown salon. Five years later, she and business partner Olethea White opened the Rose Meta House of Beauty in a renovated brownstone mansion on West 148th Street, which offered luxury amenities and treated each customer with the utmost care and respect.

In 1955, Rose Morgan, now as sole owner, opened the “ultra modern” Rose Morgan House of Beauty. The grand opening of the quarter-million dollar facility was attended by over 10,000 people, including the mayor. When she married world-champion boxer Joe Louis in a lavish star-studded wedding later that year, their celebrity attracted still more customers. Although their tumultuous union only lasted three years, Louis encouraged her to add a separate grooming studio for men that sold male-oriented products and guaranteed no wait-time for service. Like many of her predecessors, Morgan supported many worthy causes. In addition to fundraising for the NAACP, she co-founded the Freedom National Bank, a Black-owned commercial bank that helped secure financing for Black entrepreneurs.

Sources: Ellen Terrell, “Black Beauty: Brief History of the African American Beauty Industry,” Library of Congress (2020); Journal News, March 16, 1957; New York Age, Aug. 3, 1957; Nichelle Gainer, “Overlooked No More: Rose Morgan, a Pioneer in Hairdressing and Harlem,” New York Times (April 10, 2019).

In the 1960s to 1970s, the rise of the Black Power Movement stimulated public debate about how to advance the freedom struggle and promote Black culture and identity. Beauty parlors and barber shops around the country became important venues for these discussions, where people from different generations and social classes crossed paths. Many Black Americans now celebrated their African heritage, including adopting traditional fashions and hair styles. Political activists, like Angela Davis who proudly wore a prominent Afro, also popularized wearing hair in its natural state. Black hairdressers and barbers, in turn, changed their methods to embrace more holistic approaches to beauty culture. At the same time, mainstream society viewed women who adopted Afros and other natural hair styles as non-conformists, who were resistant to the status quo and needed to be regulated.

Since the 1980s, a revival of the “natural hair movement,” widely discussed in online forums, has sought to combat internalized negative images that still surround natural hair in some venues, especially after several high-profile lawsuits initiated by women who were pressured to conform, or even fired, by employers with discriminatory dress codes. These online forums offer hair care tutorials, recommendations for products best suited for natural curls, and advice on how to transition from processed to natural hair. They also provide a space for Black women to share their life experiences, including the adversities they’ve encountered as professional women wearing historically Black hairstyles in the workplace.

Joe Dudley and Eunice Dudley

Joe Dudley and Eunice (nèe Mosley) Dudley began their African American hair care company mixing shampoo and hair care formulas in their kitchen. Born in 1937 near Beaufort, North Carolina, Joe Dudley overcame a speech impairment with the aid of his mother and later majored in business administration at North Carolina A&T State University. Eunice was born the seventh of nine children in Selma, Alabama and attended Talladega College. In 1957, Joe traveled to New York, where he met a salesman selling a hair care line owned by Samuel B. Fuller, an African American entrepreneur. After investing $10 in his own sales kit, Joe earned enough money to continue his studies. Eunice, meanwhile, was also selling Fuller products door-to-door. After they graduated and married, Joe and Eunice moved to New York City in 1962. Working now full-time for Fuller Products, they travelled regularly to cities with poor sales to determine how to attract more customers. In 1967, they moved back to North Carolina and started a Fuller distributorship. When the company was unable to keep up with consumer demand, the Dudleys began making their own products in their kitchen, enlisting their children to help with packaging and sales. By 1976, the Dudleys had developed a sales force of over 400 along with a beauty school and a chain of beauty supply stores across the Southeast. In the 1980s, they bought the rights to Fuller Products and opened Dudley Beauty Schools in eight locations.

Joe and Eunice sample products in 1972, when their company grossed a million in a year. Courtesy of Greensboro News & Record.

Gathering Places

Black barber and beauty shops have long served as centers of community and crucibles of social justice activism. In 1941, for example, 50,000 African Americans turned out for a pro-union march on Washington, D.C., after labor leaders sent promotional flyers to beauty parlors in 18 cities and visited all the beauty and barber shops in Harlem; the publicity campaign was spearheaded by A. Philip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters, whose wife Lucille was a prominent New York hairdresser. In the 1960s, Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee credited conversations at his local barber shop for his political awakening.

These establishments have also provided inspiration to writers, artists, musicians, and film makers. For his MA thesis at NYU’s Graduate Film School, for example, Spike Lee made a film entitled “Joe’s Bed-Stuy Barbershop: We Cut Heads,” that reflected on their significance to the Black community–a theme that he later revisited in several motion pictures.

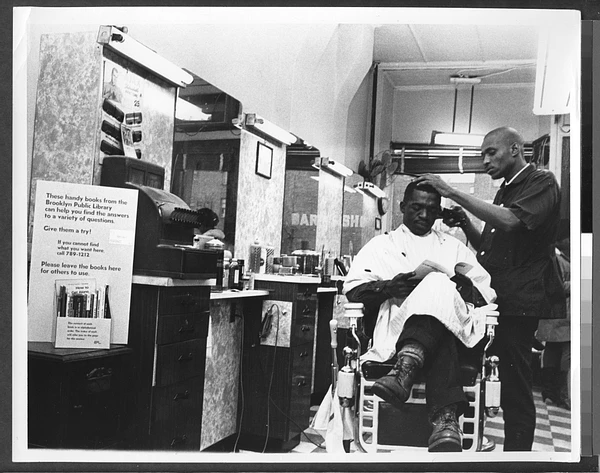

Barber shops and beauty parlors have also been important educational venues. Local health officials relied on them to raise awareness of wellness campaigns. The Brooklyn Public Library likewise brought lending books to them to make its resources more accessible to under-served communities.

Today, Barbershop Books–a leader in the field of early literacy and winner of the National Book Foundation’s “Innovations in Reading Prize”–is keeping that tradition alive. Founded by Alvin Irby, the organization supports fun reading experiences for thousands of children every year through its national network of barber shops, schools, and community organizations. Its mission is to inspire Black boys and other vulnerable children to read for fun through child-centered, culturally responsive, and community-based programming and content.

Business & Community in Southampton

The Black community in Southampton has a rich cultural legacy that dates to the mid-17th century. The first Africans were brought here in bondage by early English settlers who forced them to the land which was taken from the Shinnecock and other Native inhabitants. By the mid-18th century, people of African descent, then over 12% of Suffolk County’s population, significantly contributed to the region’s economic development, including in agriculture, household production, and maritime enterprises (including fishing, whaling, and shipbuilding). Even after 1827, when slavery finally ended in New York, Black Long Islanders had limited access to employment opportunities, land, or capital. Despite these obstacles, however, they began to launch their own businesses, acquire land and houses, and organize churches, mutual aid organizations, and civic groups. Consequently, some of the nation’s oldest historically Black communities are on Long Island.

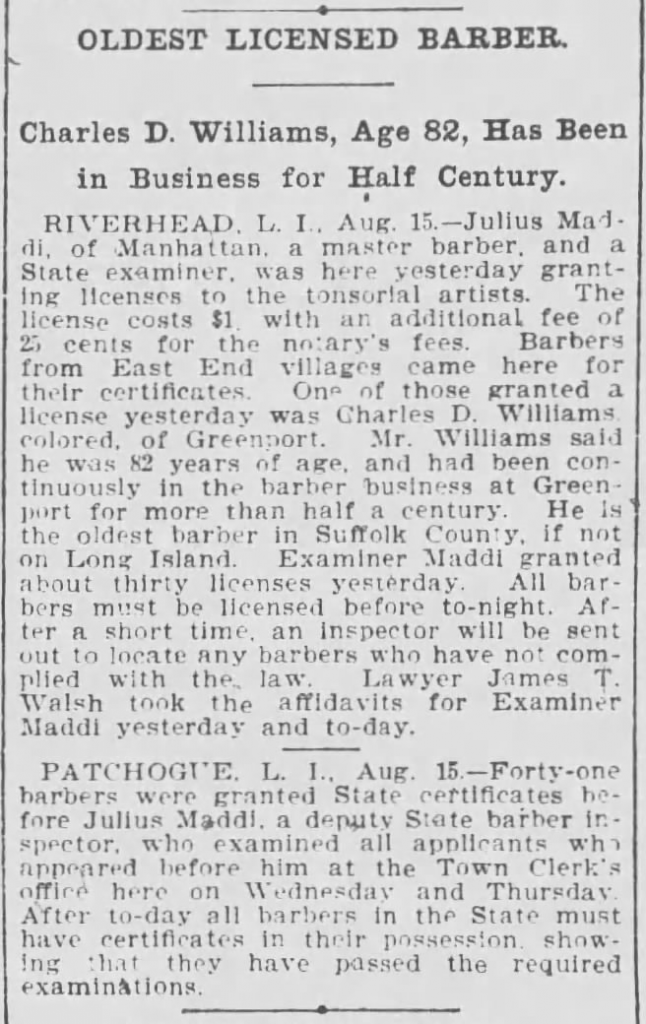

By the turn of the 20th century, a Black barber shop was already one of the oldest businesses in Suffolk County. Founded in 1844, its owner was Charles D. Williams, a native Long Islander. At the turn of the century, Williams, then in his eighties, was still pursuing “his trade with the same skill as when a young man.” Nevertheless, in 1903, when New York State implemented new licensing rules, he was suddenly required to pay onerous fees and pass a written test to continue his life-long trade. While overtly a health and safety measure, the law was intended to push people of color out of the increasingly competitive barbering trade. After 60 years behind the barber’s chair, Williams readily overcame this hurdle and was able to stay in business. During the 20th century, Long Island saw the development of a many Black-owned businesses supported by a flourishing Black middle class, despite rising real estate prices make sustaining once tight-knit communities more difficult. It is thus very important to preserve and honor this significant aspect of Long Island’s history and cultural heritage.

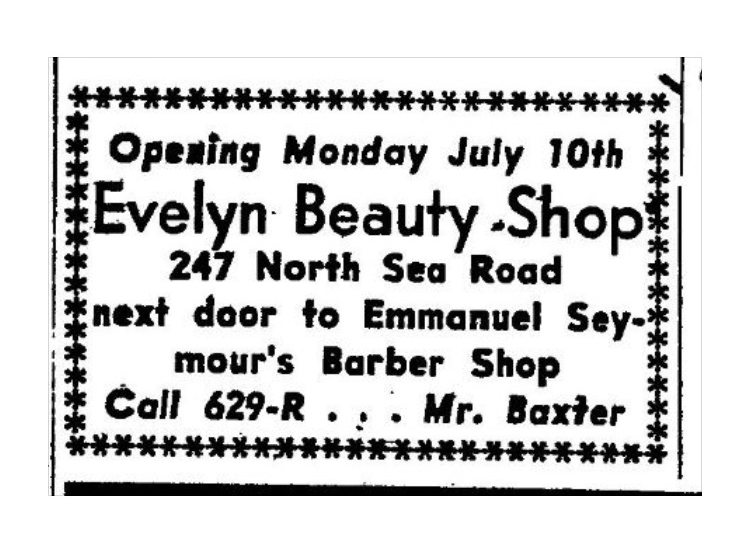

Emanuel Seymore

Emanuel Seymore, founder of this barber shop/beauty parlor, came to Southampton as part of the Great Migration in the early 20th century. His family was from Currituck, North Carolina—a Tidewater Region of plantations, shipyards, and fisheries that historically relied on slave labor. At the time, African Americans in the North were beginning to make some meaningful gains, while those in the rural South still had little access to education and landownership. In hopes of greater opportunities, the Seymores made the difficult decision to leave home and join the exodus to the North. Like many rural Southerners, they first moved to bustling New York City but then relocated to the more peaceful environs of eastern Long Island. At the time, jobs were readily available in familiar agriculture and maritime enterprises. After settling in Southampton, Emanuel found initially employment as a farm hand and his wife was a homemaker and worked part-time as a housekeeper for a private family. Together, they bought a house on Hillcrest Avenue and in 1930 celebrated the birth of their first child. Around 1947, Emanuel Seymore, then in his late thirties, opened the barber shop North Sea Road and built up a thriving multi-service business.

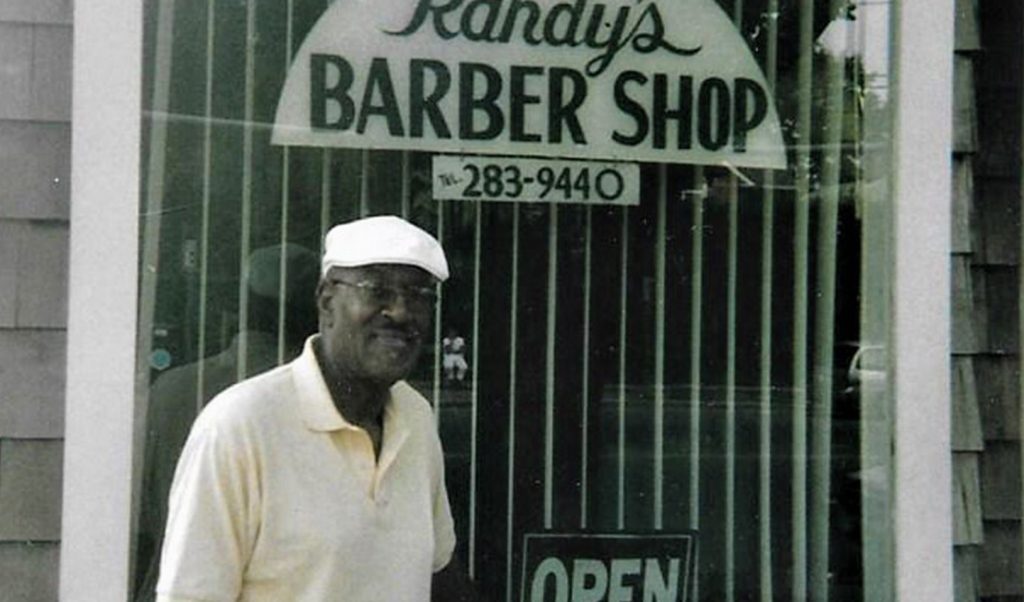

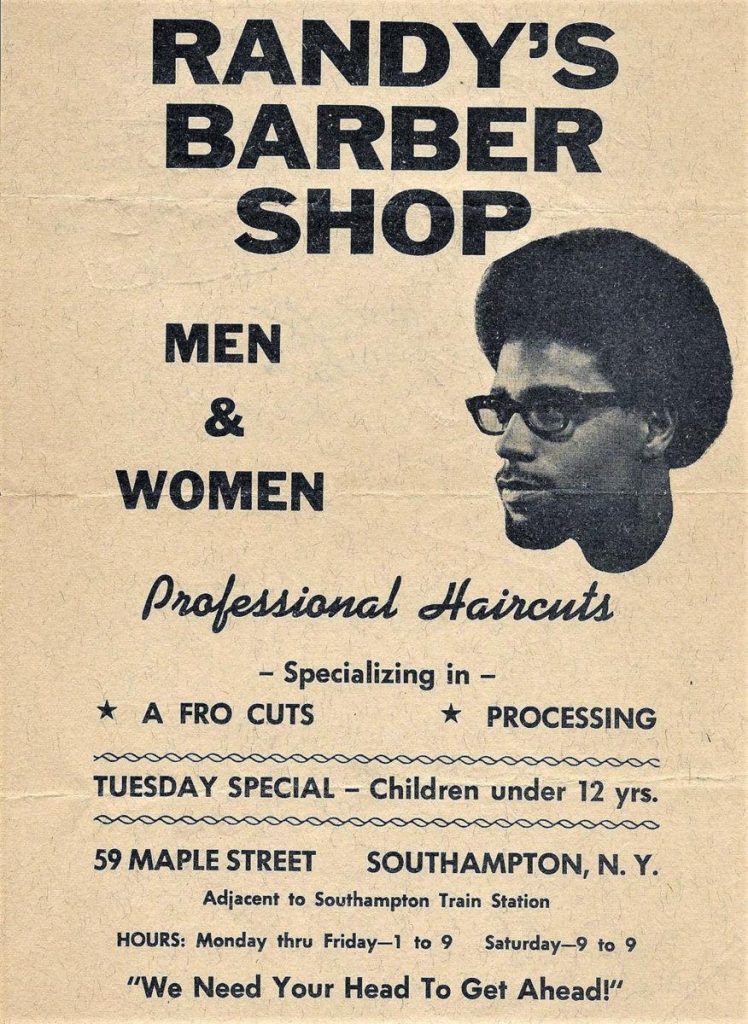

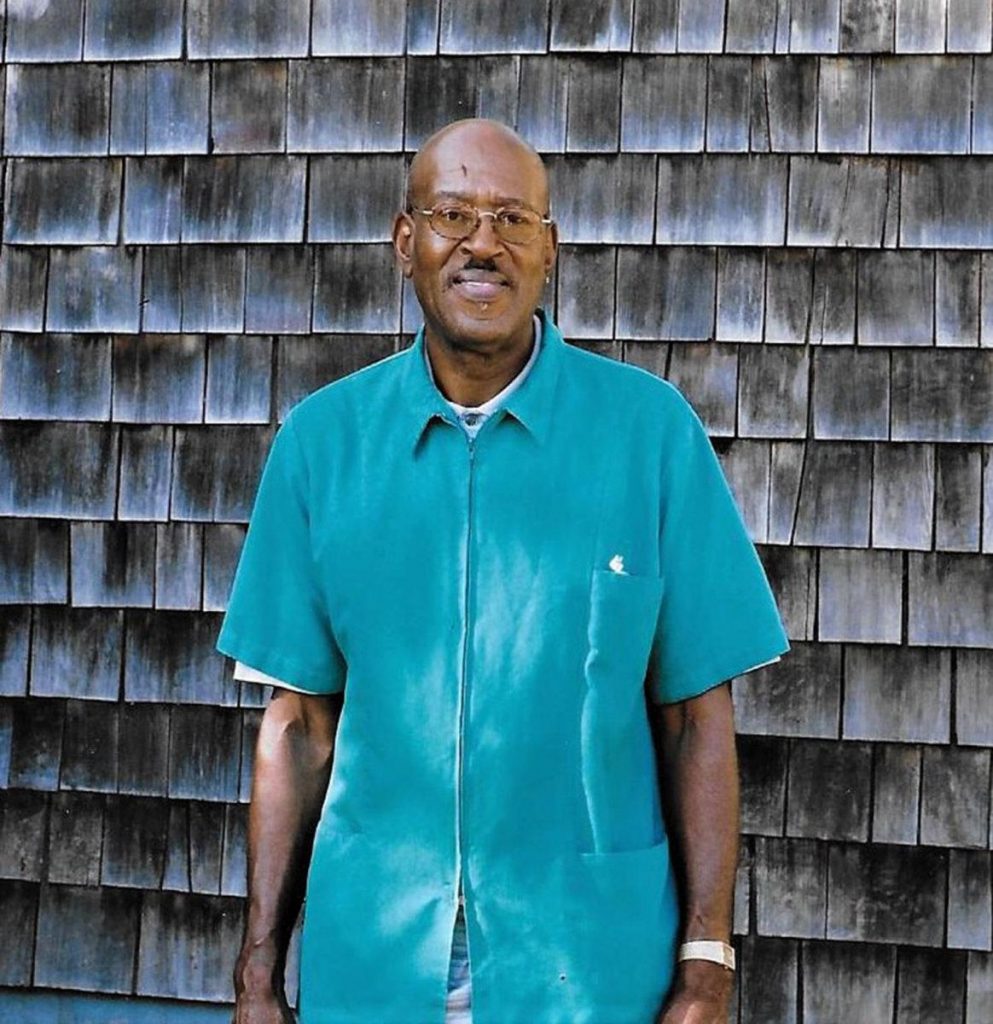

Randolph “Randy” Conquest

Randolph “Randy” Conquest became the barber/beauty shop’s second owner, after Emanuel Seymore retired around 1977. After the Conquest family moved to Long Island from Virginia, Randy was born in East Patchogue in 1937. During his early years, his family lived and worked on the 45-acre Gallo Duck Farm. His daily chores included chasing thousands of ducks into their pens every night–a responsibility that did not inspire him to become a farmer. When he was about 12 years old, his family moved to Patchogue. Both he and John, his younger brother, both attended Patchogue High School, where they excelled in basketball.

After graduating from Patchogue High School in 1956, Randy enrolled in a nine-month course at the Tyler Barber School in New York City. He did very well and enjoyed the work. Not everyone shared his abilities, however, for instance, as Randy later recalled, one classmate “really wanted to be a barber, but he was too heavy-handed. He didn’t have the gift; I call it a gift because it’s not the type of thing that can really be taught. You just have to have the feel for it; it’s really an art. You either have it or you don’t. I felt sad for [him] because he really wanted to be a barber.” After securing his state license, Randy found employment at several different barber shops, from Long Island to the Bronx. To hone his skills, as he recalled, “I used to go to all of the best barber shops in New York City and watch the master barbers and hair stylists before I started trying things on my own. I wanted to learn how to do things the right way.” In 1969, after twelve years of working for others, he finally opened his own shop on Halsey Street in Southampton. His brother John, meanwhile, pursued a career as a school principal and coach in the South County School District.

When Emanuel Seymore retired around 1977, Randy bought the building and moved his business to North Sea Road. For the next 27 years, he opened his premises as a thriving enterprise and a vibrant gathering place for the local Black community. The role of Randy’s Barber Shop went beyond providing hair care services. He regularly employed and mentored young men in the art of barbering. The knowledge and experience they acquired working for Randy improved these young men’s economic opportunities and allowed them to open their own businesses. “There was a young man, Clyde Hallman, whose hair I cut,” Conquest recalled, “One day when he came in for a haircut, he told me he liked to cut hair, [so] I took him on as an apprentice. He had the gift. He was a natural!” After mastering the craft, Clyde continued to work with Randy for 35 years. Among those who apprenticed with Randy Conquest were Charlie Green, Augustus (Gus) Stewart, Joey McCoy, Artie Williams, and Terrell Jones.

True to the long tradition of Black barber shops and beauty parlors, Randy’s Barber Shop was also an important hotspot for social networking and community development. Randy, for example, was involved with the local association of Black business owners. He also encouraged civic engagement and emphasized the importance of voting and participating in the democratic process. “I always tried around voting time, to bring up the subject of voting,” as he explained, “because I feel it is always important to vote because of what my forefathers went through… [when] they couldn’t vote. . . . [Today, many people] don’t realize their vote does count [and] your presence in the polling place counts.”

For much of the 20th century, Emanuel Seymore and later Randy Conquest sustained their businesses thanks both to local residents and seasonal migrant workers who patronized their establishments. Along Eastern Long Island, the demand for labor at farms during and after World War II attracted hundreds of farmworkers every year, some of whom stayed on and settled in the region. Initially, the majority of migrants were African Americans from southern states, especially Florida, seeking job opportunities. By the early 1960s, however, workers increasingly arrived from Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Mexico, and elsewhere in the Caribbean and Latin America. To meet the growing demand for worker housing, in 1942 the New York State Farm Security Administration approved the creation of low-cost labor camps in different areas of New York State, including Suffolk County. By 1960, Southampton alone had thirteen registered migrant labor camps that could accommodate approximately 260 workers. In many cases, living conditions at migrant camps were poor and laborers were exploited by the farm owners. At the end of a long week in the fields, many migrant workers would visit the local barber shop or beauty parlor for some personal care. They also enjoyed spending weekend evenings at the juke joint for refreshments and entertainment. As that suggests, the migrant workers significantly contributed to the local economies of nearby towns and proved very beneficial for local Southampton businesses. As Randy recalled, “In the summertime, there used to be an influx of people who used to come here from Florida just for work, and that really helped my business. Then we also had a lot of migrant camps, and that was more heads in the barber shop!”

After Randy retired in 2006, Gus Stewart briefly operated the barber shop before moving away. At that point, Randy planned to sell the property. Local residents, however, did not want to see this beloved neighborhood feature disappear forever. Recognizing its historical significance, Gloria and Bonnie Cannon proposed trying to save it. Inspired by the possibility, Brenda Simmons, whose Aunt Evelyn ran the beauty salon, spearheaded efforts to preserve and transform the site into a museum of African American history. In October 2006, the Town of Southampton purchased the building, the Village of Southampton awarded it historical landmark status, and, after eight years of fundraising, restoration efforts began. The groundbreaking ceremony for the future museum was held on July 7, 2018.

MEMORIES

Brenda Simmons (2021): Saturday, the day before church, was the day my Mom set aside to do our hair. Washing, drying, then straightening. We were five girls, but my youngest sister didn’t get her hair straightened, just washed and ponytails. So this is how it went–because me and my sister Sandra’s hair texture was less “curlier” (aka “nappy /thicker”) she did our hair first because it took less time. Then she did my oldest sister Jamie and younger sister’s hair. Sandra and I would sit around watch and laugh as my sister would cry because the combing out alone was torture. Sometimes if Mom got the hot comb a bit too close to the scalp or ear, it would burn. Ow!

My Aunt Evelyn, who worked in the beauty parlor, was soft spoken and kind but could be very out spoken and bold when it was needed. She was what we called “prissy,” meaning extremely lady-like. She used to teach us the importance of respecting yourself as a young lady. How to cross your legs, for example, and not sit with them open. I’m very bowlegged so I used to have a very hard time “crossing my legs.” At the time, I felt very frustrated, but eventually she gave me my solution — to cross my feet instead of the knee-level crossing.

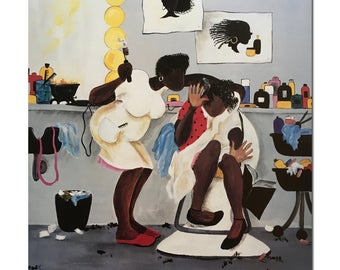

“Burn You, Baby?,” Annie F. Lee (1935-2014). Known for lively scenes of daily life, like this one of a beautician straightening a girl’s hair with a hot comb, Lee became a professional artist at age 40, while working full-time, raising children, and attending college at night.

Source: Historymakers.org

Also I should explain the importance of this building having 2 front doors! The right door was the entrance to the beauty parlor. And the left door was the entrance to the barber shop–with a wall dividing the two! Since it was well known that young ladies do not mingle with the “men,” girls were prohibited to ever go on the barber-shop side–even though the wall was thin enough to sorta hear mumbling, but not really conversation. But my auntie would ask me on occasion to bring Mr. Emanuel something and I got the “privilege” of going beyond the divide wall . . . . I used to come to my Auntie’s shop to answer the phones, write down appointments for her, and help with errands, such as going to the store to buy coffee and her favorite “juicy fruit” chewing gum. The best part was she would always give me extra to get “sweeties/goodies” for myself. . . My Auntie was known for popping gum — Loud And Fast! Sometimes the clicking of the curling iron and popping of her gum sounded like a rhythmic beat. I can almost smell the grease burning that she used to dip the curling iron in to help make the curls tight and less likely to fall or get loose. . . .

I remember sitting in the front window on the “right side,” sometimes reading the latest Jet or Ebony magazines that I’d always neatly line up, like a fan, in date order. Their powerful stories and photos of prosperous Black men and women–actors, actresses, lawyers, and entrepreneurs–left strong lasting images on our young minds and, most importantly, on our spirits. Lastly, I vividly recall the thin brown-backed chairs lined up against Ms. Katherine’s divider, which was designated as the waiting area. And sometimes the wait was long–which was an expected norm. But much was gained by time spent in Ms. Evelyn’s shop. And you always knew that when you left there, she would make you feel like the prettiest little girl in the world!

We were in our teens when he bought the shop on 245 North Sea Avenue. By then, he was pretty adept at doing women’s hair, so I had my hair done free. I remember my Dad worked hard--sometimes until late at night--and I saw the things hard work brings if you stay with it. He instilled that on me and my siblings Dean and Randi. My sister was named after him but I look most like him. . . I remember as a little girl getting my hair done at Evelyn’s Beauty parlor . . . and going into the juke joint to get candy, hearing music, and seeing people dancing . . . . But Dad kept us in check for sure. He always told me to get good grades and stressed college. I went that route but we all were successful in our own ventures in life. We wanted our Dad to be proud of us!

Juke Joints

Between the 1940s and 1960s, on Eastern Long Island, juke joints became the places where African Americans ate, danced, and socialized after arduous days of intense and poorly remunerated labor. At 245 North Sea Road in Southampton, Arthur “Fives” Robinson, with the support of Emanuel Seymore, opened one of the junk joints of the Hamptons. Contiguous to the barber shop and the beauty shop, the junk joint, run by “Fives,” was the place where laborers from potato farms from the East End and domestic workers spent their spare time and lifted their spirits. On Saturdays and Sundays, African Americans from the area and seasonal workers spent their nights enjoying the popular ham hock and beans made at the place and listening to the music of Big Men, Little Curtis & The Blues, or Snooks Eaglin. According to Randy Conquest, the place always had a “happy atmosphere.”

Additional Resources

https://smallbusiness.com/history-etcetera/early-role-black-owned-barbershop-african-american-entrepreneurship/

https://www.businesshalloffame.org/alonzo-herndon

https://barbershopbooks.org/ted-talk-with-alvin-irby/

https://www.thehistorymakers.org/biography/annie-lee-41

https://www.thehistorymakers.org/biography/rose-morgan-39

ArChives

Explore our past events and exhibits

BLACK ANGELS OVER TUSKEGEE

HAMPTONS ARTS NETWORK THAW FEST

Southampton Historical Museum

SAAM 9TH ANNUAL FILM FESTIVAL

Hosted at the Southampton Cultural Center September 2014

watchAFRICAN AMERICAN ART

of Peter Marino